Michael Sankowski, writing at Monetary Realism, critiqued using futures contracts to target nominal GDP. Unfortunately, he misunderstood the proposal. He thought that the Fed would trade the futures contracts at a fixed price right up until the time of settlement. For example, he considered the Fed trading a contract on third quarter 2012 nominal GDP up until the preliminary estimate is announced in late October. He imagined Goldman Sachs putting up $5 billion in margin the day before the announcement, with some huge leverage. And then the result would be a $500 billion payday for Goldman Sachs.

However, the proposal has the Fed cease trading the contract on the third quarter of 2012 before that quarter begins, with recent proposals being three quarters before, at the end of the third quarter of 2011. During the fourth quarter of 2012, the Fed would be trading contracts on the fourth quarter of 2013. Of course, the system could be set up with longer or shorter lags. Sumner often mentions a two year lag. Still, no version suggests less than a one quarter lag. Anyway, the notion that Goldman Sachs, or anyone else, would get wind of tomorrow's announcement of nominal GDP and then trade some huge amount with the Fed the day before is inconsistent with any sensible version of the proposal.

Sankowski's understanding of leverage in futures markets is quite different from mine. In his example, Goldman Sachs supposedly put up $5 billion in a margin account on one day and received a $500 billion return. He understands this as being 100-1 leverage--or perhaps the implication of 100-1 leverage.

The actual proposals for futures targeting involve margin requirements based upon the variance of the targeted macroeconomic variable. If Goldman Sachs takes a position that could generate a $500 billion profit, there is also a chance of a $500 billion loss. The margin requirement for that position would be of the same order of magnitude. For example, suppose a $1000 contract pays $10 for every percent that nominal GDP deviates from target. Suppose there is only a 1 percent chance that nominal GDP will deviate more than 2 percent from target, and that is considered acceptable. The margin requirement would then be 2 percent, or a only $20 a contract. "Leverage" would be 50 to 1. A sale of $250 billion worth of contracts would require a $5 billion margin requirement. If nominal GDP was 3 percent below target, the pay off would be $7.5 billion, providing return on the margin investment of 150%. If, on the other hand, if nominal GDP was only 1 percent below target, then payoff would be $2.5 billion and the rate of return would be 50%.

For Goldman Sachs to get a $500 billion, then the deviation would have to be very large. Let's say it is 5 percent, so that it would require contracts worth $10 trillion. The margin requirement would have been $200 billion. This would be a great return for Goldman Sachs--250%. And, of course, the "cost" wouldn't be the $200 billion, which would be returned with interest. The cost is the risk that nominal GDP would have come in above target. For example, if it was 1 percent above target, the loss on a $10 trillion short position would be $100 billion.

Sankowski also discussed the possibility of using the contracts for hedging. Incredibly, he described a scenario that I understood to be "dynamic hedging." Perhaps Sankowski misspoke, but he seemed to imagine that a company would forecast losses and then sell futures contracts against nominal GDP to hedge the loss. How is that hedging? I had never even imagined such a "strategy" until Arnold Kling suggested that some traders were using it during the financial crisis. I don't remember the details, but it was something like "hedging" the losses from selling default swaps by carefully watching the news, and when risk of default increased, selling the insured bonds short. That makes just about as much sense as "portfolio insurance."

A true hedge would be companies nominal GDP futures contracts on the anticipation that when nominal GDP was below target, sales and profits would be low. And if nominal GDP came in above target, sales and profits would be high. This would reduce the variability of profits on operations plus the net return on the futures contract. But waiting to find out that profits will be low and selling futures--that isn't hedging.

Sankowski's entire approach to the analysis seemed to be about whether futures exchanges would find it advantages to introduce these contracts. Would the member/owners find opportunity to profit from commissions or at the expensive of hedgers? Well, that is hardly important. The purpose of futures targeting is not for a central bank to make money from commissions or at the expense of traders. The primary purpose is to constrain the central bank to seek the targeted goal. The secondary purpose is to provide an opportunity for market participants to reveal their expectations regarding nominal GDP, so that the central bank may adjust monetary conditions according to those expectations.

Sunday, July 15, 2012

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

Selgin and Dougherty's Diagrams

For the discussion regarding "reflation," George Selgin produced two graphs and Tom Dougherty produced one.

Here is Selgin's first graph:

Here is Selgin's first graph:

He interpreted this diagram as showing that while nominal GDP has recovered relative to its initial peak and wages have grown more slowly, wages have not grown slowly enough.

Dougherty complained that everyone was using wages for nonsupervisory and production workers, when all wages is also available. He provided the following diagram (in a link to a comment on Sumner's blog.)

Aside from being a better measure of the whole labor market, the diagram appeared to show that this broader measure of wages has slowed its growth rate enough so that it is now in alignment with the recovery in nominal GDP. Of course, it is interesting how different the nominal GDP chart appears. (The problem with the data series on wages is that it only starts in 2006, so there is no way to observe its behavior during the Great Moderation or longer.)

Selgin then worked some more on his chart, still using the narrower measure of hourly wages.

Now both nominal GDP and wages are indexed at 100 in 2005 and it shows that nominal GDP has grown more than hourly wages! Surely, there is by now enough nominal GDP! Nominal GDP is about 25 percent higher, and hourly wages are only about 23 percent higher.

Unfortunately, nominal GDP has been growing faster than hourly wages for a long time. Below is a chart looking at the growth rates of both and the trends from the Great Moderation (1985 to the end of 2007)

Nominal GDP grew a bit more than 5 percent and hourly wages a bit more than 3 percent. Over the period from 2005 to 2012, this would create a gap of nearly 18 percent. (2 percent a year compounded over 7 years) In Selgin's last diagram, the growing gap between the index for nominal GDP and hourly wages before the recession is what would be expected given their different trends. Even with the slow down in wage growth, I would think, at first pass, that nominal GDP would need to have increase about 18% more, rather than just 3% more.

Why the difference in growth rates? The most basic reason is population growth. If each worker makes 3 percent more, and there are 1 percent more workers, then their incomes are going to grow 4 percent. Why is wage growth 2 percent less than nominal GDP growth? My guess is that it is mostly a trend in nonwage compensation over the period.

What about the difference between production and supervisory wages versus total wages?

There isn't much pre-recession data to work up a trend for total hourly wages, but it was growing slightly more than wages for production and nonsupervisory employees during the Great Moderation. The slow down in the growth of the two series is very similar.

In my view, the best way to look at these things is to compare the growth paths and trends. When there is a big shift in trends, growth rates don't say much, and it is pretty clear that indexed diagrams don't help much either.

Marcus Nunes has a great post about Selgin's diagrams showing plenty of useful charts.

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

Selgin on Monetary Stimulus

George Selgin has been skeptical of arguments that the Fed needs to do more at "this time" for a long time. Market Monetarists, on the other hand, have been insisting that the Fed "do more" since 2008 and have not stopped. Selgin brings up the issue here. (Lars Christensen responds here. And Scott Sumner responds here.)

However, as time has passed, there have been adjustments in the view as to "how much" more the Fed should do. Sumner has become very "conservative," on the matter, arguing for a couple of years of 7 percent growth and then 5 percent from then on out. Beckworth has generally advocated shifting back up to the growth trend of the Great Moderation, which would be very rapid growth in nominal GDP during the adjustment period. My own, somewhat politicized view, is that we should have a Reagan/Volcker recovery in nominal GDP, and then shift to a 3 percent growth path for a new "Great Moderation," this time with something much closer to the price stability promised last time.

To my reading, by the time the recovery started, Selgin thought it least bad to just accept the new baseline and then allow for slow, steady nominal income growth from there. Perhaps at his preferred one percent trend. (I may have been reading too much into his remarks.) To me, this is the implication of growth rate targeting.

Nominal GDP growth rate targeting would be for nominal GDP to grow the targeted amount from wherever it happens to be. While level targeting is often characterized in terms of catch up growth (or slowing,) I think this sort of definition makes growth rate targeting somehow fundamental. To me, level targeting means that the target is a series of levels going out into the future. Pick a future date, and there is a target level associated with that date. You can look at the rate of increase in the target levels. You can calculate a growth rate between some current value of nominal GDP and the targeted level at some future date. But the target for any future date is the level--not some growth rate from the current value.

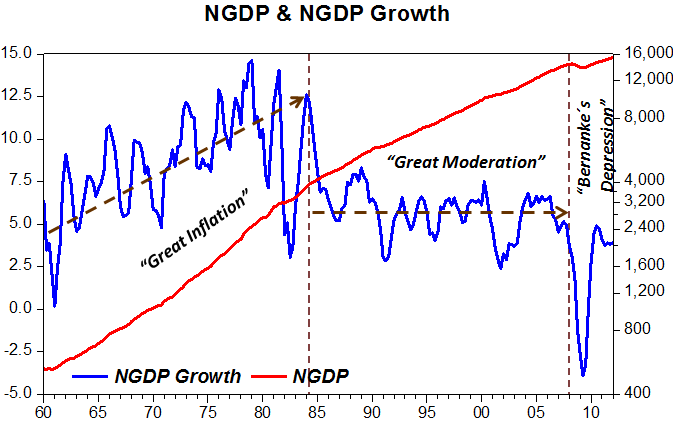

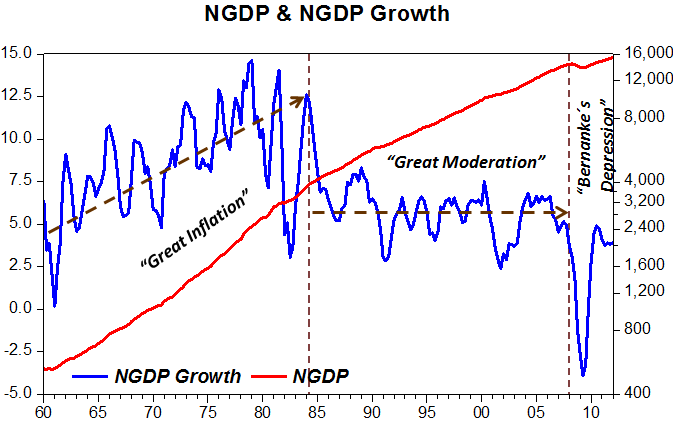

From a growth rate targeting perspective, monetary policy isn't doing too bad. The diagram below shows the growth rate of nominal GDP along with the trend from the beginning of 2005 to the end of 2007.

However, as time has passed, there have been adjustments in the view as to "how much" more the Fed should do. Sumner has become very "conservative," on the matter, arguing for a couple of years of 7 percent growth and then 5 percent from then on out. Beckworth has generally advocated shifting back up to the growth trend of the Great Moderation, which would be very rapid growth in nominal GDP during the adjustment period. My own, somewhat politicized view, is that we should have a Reagan/Volcker recovery in nominal GDP, and then shift to a 3 percent growth path for a new "Great Moderation," this time with something much closer to the price stability promised last time.

To my reading, by the time the recovery started, Selgin thought it least bad to just accept the new baseline and then allow for slow, steady nominal income growth from there. Perhaps at his preferred one percent trend. (I may have been reading too much into his remarks.) To me, this is the implication of growth rate targeting.

Nominal GDP growth rate targeting would be for nominal GDP to grow the targeted amount from wherever it happens to be. While level targeting is often characterized in terms of catch up growth (or slowing,) I think this sort of definition makes growth rate targeting somehow fundamental. To me, level targeting means that the target is a series of levels going out into the future. Pick a future date, and there is a target level associated with that date. You can look at the rate of increase in the target levels. You can calculate a growth rate between some current value of nominal GDP and the targeted level at some future date. But the target for any future date is the level--not some growth rate from the current value.

From a growth rate targeting perspective, monetary policy isn't doing too bad. The diagram below shows the growth rate of nominal GDP along with the trend from the beginning of 2005 to the end of 2007.

Sure, things were really bad at the end of 2008, but now growth is close to trend. For those like Selgin and I, who believe that the trend was too inflationary anyway, this more recent growth rate is better! In fact, it is a bit high if anything.

Of course, Market Monetarists focus on the growth path. And it shows a very different picture.

During the Great Moderation, nominal GDP stayed on a very stable growth path. And now, it has shifted to a significantly lower growth path with a slightly lower growth rate. Market Monetarists favor level targeting and so it is natural for us to insist that the Fed should have kept the economy on the trend growth path and reversed any deviation. The only way to reverse any negative deviation is for nominal GDP to grow faster than trend.

Selgin argues that wages have grown more slowly since the beginning of the recession--not at all at the University of Georgia. With nominal wages growing so slowly, should the economy recover?

Here are hourly wages for production and nonsupervisory employees. First the growth rate:

While the average is higher than for the University of Georgia, it is still far below the 3 percent trend and has been since the end of the recession. So, with nominal GDP growing more than 4 percent and wages growing less than 2 percent, surely the economy should have recovered? Well, no, the economy should be recovering, and it is. Employment has been rising--just very slowly.

Now, if we look at the growth path of hourly wages, then the problem becomes obvious.

If wages had fallen below their trend as much as nominal GDP did, then wages would have adjusted to the new growth path. In fact, nominal wages are only about 2.6 percent below the trend of the Great Moderation. They just have about 12 percent to go. If nominal GDP grows 5 percent per year, and nominal wages grow 1 percent, then that should take only about 3 years. With 4 percent nominal GDP growth and 2 percent wage growth, then it could be more like six years.

Inflation, using the GDP chain-type deflator is here:

While inflation has averaged well below trend since the end of the recession, it has had a few quarters slightly above trend. And the last one, was almost right at the 2 percent target! The Fed is sure doing a great job of keeping inflation from rising too high! And there was only one quarter of deflation.

What about the price level relative to trend?

The price level is 2.2 percent below the trend of the Great Recession. Interestingly, this adjustment is smaller than the adjustment in wages, at least the hourly wages of production and nonsupervisory employees.

The gaps between current levels and the trend growth path of the Great Moderation are below:

Assuming potential output had continued on the growth path of the Great Moderation, then the price level would need to be approximately 13 percent further below its trend for real expenditure to be equal to potential output given this huge drop. Wages would need to be approximately that much lower too, relative to trend.

Market Monetarists are well aware that it is possible that potential output has fallen about 13 percent below the trend of the Great Moderation. (The CBO estimate of potential output is about 7 percent below the trend of the Great Moderation.)

And perhaps the equilibrium quantity of labor has fallen some huge amount too. The supply of labor decreased along with the demand, or the supply of labor is very elastic.

But I don't believe it.

As I said before, I think a traditional recovery in nominal expenditure, like that of the Reagan-Volcker years, would be appropriate. And then we should move to a long run, noninflationary growth path for nominal GDP.

Sunday, July 8, 2012

Frictions and Relative Price Distortions

In a comment on an earlier post, Robert paraphrases Williamson, who argued that while optimal monetary policy should generate a zero nominal interest rate by creating expected deflation equal to the equilibrium real interest rate, "frictions" exist which will distort relative prices. Avoiding those distortions might require a second best policy.

Assuming Williamson didn't misspeak, I think he is wrong. Patinkin explained this years ago. Assume that all relative prices, including real wages, are at equilibrium. The real quantity of money equals the demand to hold money. Now, the nominal quantity of money falls 10 percent. No money price or wage changes at all. The real quantity of money also falls 10 percent, and to rebuild money balances, less is spent on goods and services. Firms won't produce what they can't sell, and so the surpluses of goods and services result in less production. Firms won't pay people who aren't producing, so employment falls as well.

There has been no change in any money price or wage, so all relative prices, including real wages remain at their equilibrium values. The decrease in the quantity of money has depressed real output and employment below their equilibrium values, but with no distortion of any relative price. In particular, there is a surplus of labor even though real wages are at their equilibrium value.

Now, assume that money wages and prices are not perfectly rigid, but they are all equally sticky. And so, the surpluses of goods and services and labor result in all prices and wages slowly falling. This increases real money balances, and results in a recovery of both production and employment towards equilibrium levels. Once prices and wages have all fallen enough, the real quantity of money has risen back to its initial value, as have real expenditures and real output.

However, at no point during the process were relative prices or real wages distorted. They stayed the absolute same. By assumption, they all adjusted at the same rate. The problem was entirely one of an inadequate real quantity of money to match the real demand to hold money, and never was a problem with distorted relative prices.

Now, it is likely that prices are not equally flexible, and so it is also likely that the process would involve some distortion in relative prices. The more flexible prices fall more and the more rigid prices fall less. The relative prices of the more flexible money prices fall and the relative prices of the more rigid money prices rise. But it is not these relative price distortions that are the fundamental problem.

For example, suppose regulation was used to slow the rate of decrease in the more flexible money prices. Would that help? It would fix the relative price distortion. To take that to an extreme, price floors on all goods and resources would keep relative prices and real wages at equilibrium. Would that solve the problem? Permanent depression?

Now, if there is some means to get the rigid money prices to adjust faster, than would fix the relative price distortion at the same time it hastened the recovery of real money balances. But it is that last part that was the problem.

Of course, reversing the initial 10 percent decrease in the quantity of money, or better yet, avoiding it altogether, would be better approaches.

Assuming Williamson didn't misspeak, I think he is wrong. Patinkin explained this years ago. Assume that all relative prices, including real wages, are at equilibrium. The real quantity of money equals the demand to hold money. Now, the nominal quantity of money falls 10 percent. No money price or wage changes at all. The real quantity of money also falls 10 percent, and to rebuild money balances, less is spent on goods and services. Firms won't produce what they can't sell, and so the surpluses of goods and services result in less production. Firms won't pay people who aren't producing, so employment falls as well.

There has been no change in any money price or wage, so all relative prices, including real wages remain at their equilibrium values. The decrease in the quantity of money has depressed real output and employment below their equilibrium values, but with no distortion of any relative price. In particular, there is a surplus of labor even though real wages are at their equilibrium value.

Now, assume that money wages and prices are not perfectly rigid, but they are all equally sticky. And so, the surpluses of goods and services and labor result in all prices and wages slowly falling. This increases real money balances, and results in a recovery of both production and employment towards equilibrium levels. Once prices and wages have all fallen enough, the real quantity of money has risen back to its initial value, as have real expenditures and real output.

However, at no point during the process were relative prices or real wages distorted. They stayed the absolute same. By assumption, they all adjusted at the same rate. The problem was entirely one of an inadequate real quantity of money to match the real demand to hold money, and never was a problem with distorted relative prices.

Now, it is likely that prices are not equally flexible, and so it is also likely that the process would involve some distortion in relative prices. The more flexible prices fall more and the more rigid prices fall less. The relative prices of the more flexible money prices fall and the relative prices of the more rigid money prices rise. But it is not these relative price distortions that are the fundamental problem.

For example, suppose regulation was used to slow the rate of decrease in the more flexible money prices. Would that help? It would fix the relative price distortion. To take that to an extreme, price floors on all goods and resources would keep relative prices and real wages at equilibrium. Would that solve the problem? Permanent depression?

Now, if there is some means to get the rigid money prices to adjust faster, than would fix the relative price distortion at the same time it hastened the recovery of real money balances. But it is that last part that was the problem.

Of course, reversing the initial 10 percent decrease in the quantity of money, or better yet, avoiding it altogether, would be better approaches.

Sumner's Monetary Theory--Long and Variable Leads

Scott Sumner argues that monetary policy operates with long and variable leads. However, his reform proposal, index futures targeting, was initially developed years ago when Sumner took a more traditional approach. Changes in the quantity of money today cause changes in spending on output and prices in the future. How does futures targeting work? Trading an index futures contract today, causes changes in the quantity of money today, which in turn impacts spending on output in the future. It is that future level of spending that determines the payoffs on the futures contracts traded today.

Suppose the central bank uses a different approach. This quarter, quarter 1, it trades a futures contract defined on nominal GDP for the next quarter, quarter 2. It announces a tentative target for base money two quarters in the future, which is quarter 3.

Depending on the trades of the future contract in quarter 1, it makes adjustments in that tentative target for base money in quarter 3. If the market expects nominal GDP next quarter to be below target in quarter 2 and so has a short position on the contract, the Fed raises the tentative target for base money in quarter 3. If, on the other hand, the market is long, because it expects nominal GDP to be above target in quarter n quarter 2. the Fed lowers its tentative target for base money in quarter 3.

At the end of quarter 1, the target for base money for quarter 3 is determined. During quarter 2, nominal GDP happens, and is measured. Near the end of quarter 3, when the "final" results for nominal GDP in quarter 2 are calculated, and if nominal GDP deviated from its target, funds are shifted between those who traded the contract rewarding those who correctly predicted the deviation while imposing costs on those who got it wrong. And also, during quarter 3, the central bank uses ordinary open market operations in bonds to reach the final target for base money, which was set back at the end of quarter 1.

So, in any given quarter t, contracts are being traded for nominal GDP in quarter t+1, the target for base money is being set for quarter t+2, contracts there were made during quarter t-2 are being settled according to nominal GDP in quarter t-1, and open market operations in bonds are being made to implement the target for base money set in quarter t-2.

This system is based on Sumner's notion that nominal GDP today depends on expected nominal GDP tomorrow, and expected nominal GDP tomorrow depends on the expected quantity of money the day after. Unfortunately, the "long and variable" part of the leads suggest that today, tomorrow, and the next day, or this quarter, next quarter, and the subsequent quarter, might not be right.

I will try writing down what I think Sumner has in mind:

Nt = f(ENt+1) = z(EBt+2)

Current nominal GDP is some function of expected nominal GDP next period which is some function of expected base money two periods into the future.

What are these functions represented by f and z?

The intuition behind the f function is that current spending will not deviate much from expected future spending. It would relate to the permanent income hypothesis for consumption as well as some notion that current investment spending is driven by expected future sales. However, I would think that deviations would be best represented by a random variable, and when it makes nominal GDP move away from the expected nominal GDP for next period, it is dampened in a way that depends on the interest rate.

The z function would presumably be some kind of equation of exchange. The expectation of desired base money velocity in period 3 times the expected value of base money in period 3 determines expected nominal GDP in period 2. Of course, that points to a equation of exchange determination of nominal GDP in period 3, which is inconsistent with the spirit of the approach outlined here.

Suppose spending on output falls below target in the current quarter. Nothing can be done about that other than making sure that people believe that this will be temporary and spending on output will return to target next quarter. This dampens any such deviations, though doesn't prevent them.

Why do people expect nominal GDP to be on target next quarter? Because they believe that the Fed will create enough money the following quarter to keep nominal GDP on target next quarter.

Of course, it would seem to me that a simpler approach would be to have trades of the contract this quarter determine the quantity of base money next quarter according to expectations of nominal GDP next quarter. However, along with any contemporaneous impact of base money next quarter on nominal GDP next quarter, there would be the indirect effect of base money in subsequent quarters impacting nominal GDP next quarter.

Anyway, I hope that this very preliminary analysis will trigger more discussion Hopefully, Sumner will clarify his position. (If no one else is interested in filling in model details, I guess I will keep on working on it.)

Suppose the central bank uses a different approach. This quarter, quarter 1, it trades a futures contract defined on nominal GDP for the next quarter, quarter 2. It announces a tentative target for base money two quarters in the future, which is quarter 3.

Depending on the trades of the future contract in quarter 1, it makes adjustments in that tentative target for base money in quarter 3. If the market expects nominal GDP next quarter to be below target in quarter 2 and so has a short position on the contract, the Fed raises the tentative target for base money in quarter 3. If, on the other hand, the market is long, because it expects nominal GDP to be above target in quarter n quarter 2. the Fed lowers its tentative target for base money in quarter 3.

At the end of quarter 1, the target for base money for quarter 3 is determined. During quarter 2, nominal GDP happens, and is measured. Near the end of quarter 3, when the "final" results for nominal GDP in quarter 2 are calculated, and if nominal GDP deviated from its target, funds are shifted between those who traded the contract rewarding those who correctly predicted the deviation while imposing costs on those who got it wrong. And also, during quarter 3, the central bank uses ordinary open market operations in bonds to reach the final target for base money, which was set back at the end of quarter 1.

So, in any given quarter t, contracts are being traded for nominal GDP in quarter t+1, the target for base money is being set for quarter t+2, contracts there were made during quarter t-2 are being settled according to nominal GDP in quarter t-1, and open market operations in bonds are being made to implement the target for base money set in quarter t-2.

This system is based on Sumner's notion that nominal GDP today depends on expected nominal GDP tomorrow, and expected nominal GDP tomorrow depends on the expected quantity of money the day after. Unfortunately, the "long and variable" part of the leads suggest that today, tomorrow, and the next day, or this quarter, next quarter, and the subsequent quarter, might not be right.

I will try writing down what I think Sumner has in mind:

Nt = f(ENt+1) = z(EBt+2)

Current nominal GDP is some function of expected nominal GDP next period which is some function of expected base money two periods into the future.

What are these functions represented by f and z?

The intuition behind the f function is that current spending will not deviate much from expected future spending. It would relate to the permanent income hypothesis for consumption as well as some notion that current investment spending is driven by expected future sales. However, I would think that deviations would be best represented by a random variable, and when it makes nominal GDP move away from the expected nominal GDP for next period, it is dampened in a way that depends on the interest rate.

The z function would presumably be some kind of equation of exchange. The expectation of desired base money velocity in period 3 times the expected value of base money in period 3 determines expected nominal GDP in period 2. Of course, that points to a equation of exchange determination of nominal GDP in period 3, which is inconsistent with the spirit of the approach outlined here.

Suppose spending on output falls below target in the current quarter. Nothing can be done about that other than making sure that people believe that this will be temporary and spending on output will return to target next quarter. This dampens any such deviations, though doesn't prevent them.

Why do people expect nominal GDP to be on target next quarter? Because they believe that the Fed will create enough money the following quarter to keep nominal GDP on target next quarter.

Of course, it would seem to me that a simpler approach would be to have trades of the contract this quarter determine the quantity of base money next quarter according to expectations of nominal GDP next quarter. However, along with any contemporaneous impact of base money next quarter on nominal GDP next quarter, there would be the indirect effect of base money in subsequent quarters impacting nominal GDP next quarter.

Anyway, I hope that this very preliminary analysis will trigger more discussion Hopefully, Sumner will clarify his position. (If no one else is interested in filling in model details, I guess I will keep on working on it.)

Saturday, July 7, 2012

The "Conservative" and "Liberal" Solutions

I strongly support a monetary regime that creates slow steady growth in spending on output, and I believe that such a regime is possible. In other words, the monetary regime can and should keep spending on a stable growth path even if there are adverse fiscal and regulatory policies. Obviously, undesirable fiscal and regulatory policies have undesirable consequences, but the least bad environment remains slow, steady growth of spending on output.

However, the U.S. has a regime where the central bank likes to make periodic changes in the short and safe interest rate in order to target inflation and the output gap. Some conservatives are proposing that the output gap be dropped as a criterion, so the policy interest rate would solely be adjusted to maintain a stable inflation rate. Of course, the theory is that output gaps will push inflation away from target, and so targeting inflation automatically tends to close output gaps too.

What is the conservative approach to generating recovery? Improve the tax and regulatory climate for business. If business believes that they will be able to earn and keep more profit in the future, this will raise credit demand, even given expectations about depressed future sales. Credit demand currently depends on expectations about both future sales and the future business and regulatory climate. Improving one, given the other, should result in increased credit demand. Given the Fed's target for the interest rate, any increase in credit demand is supplied through added money creation, and tends to generate more spending on goods and services.

Unfortunately, the increased aggregate demand will tend to increase inflation. With an inflation targeting central bank, this would require an increase in the policy interest srate, which would offset the effect of the higher credit demand on spending. Of course, if inflation is currently running a bit below target, this would not be a problem.

Fortunately, the pro-business tax and regulatory changes have another effect. Not only does they tend to raise the demand for credit, they also enhance productivity, which implies an increase in aggregate supply. Now, if nominal aggregate expenditure continue on an unchanged growth path, the result of the improved supply condition would be a more rapid expansion of output and slower inflation. But with inflation targeting, instead the enhanced productivity allows for more rapid growth in nominal expenditure.

So, the improved tax and regulatory environment raises both credit demand and productivity, allowing for a more rapid recovery of spending and production at a given target for the policy rate and a given target for the inflation rate. Also, the recovery in expenditure would be self-reinforcing. That is, when firms borrow more and spend more because an improved business climate , the resulting increased sales spur further increases in credit demand. When all of this happens, it is almost certain that the policy rate would need to increase, so that spending on output doesn't grow faster than justified by the increases in productivity.

Therefore, with an improved tax and regulatory environment a rapid recovery can be generated even if the central bank targets some short and safe interest rate to keep inflation at a low and stable rate. What could go wrong? The resulting increase in credit demand and enhancement of productivity might be too small to generate a "sufficient" recovery.

What is the "liberal" approach to economic recovery? The government should borrow money and spend it on expanded social services and "public goods." The public goods would include subsidies for private goods that provide external benefits. This provides a demand for credit by the government and given the target for the policy rate, this is expansionary. New money is being created for the government to spend. While it is conceivable that the public investments would add to productivity, (certainly some could,) the typical investment is supposed to improve the quality of life for at least some segment of the population. Enhancing the ability of firms to produce the sorts of private goods whose prices are included on price indices is of secondary interest.

If inflation is currently below target, the inflationary impact of added spending on prices isn't much of a problem. Increased government spending and borrowing will raise credit demand at the target for the policy rate and spending on output. Inflation will pick up back to target at the same time real output and employment recover. However, if inflation is on target, then it is essential, from the "liberal" perspective, that the "output gap" count as a weighting factor, so that higher inflation would be permitted, at least temporarily. The gap of inflation above target would be accepted because it would reduce the gap of real output below potential. Better yet, the central bank could just raise its inflation target.

Both the "conservative" and "liberal" solutions involve policies that they support anyway. The sluggish recovery is being used as an excuse for their preferred policies. Also, the policies of each are anathema to the other. Conservatives don't want to increase the size of government. One reason is that they are opposed to the changes in taxes that would be needed to pay for it sooner or later. Liberals don't want to improve the tax and regulatory environment for business, since creating such burdens to provide benefits to favored groups (the poor and working class) is central to their purpose.

Probably most Market Monetarists favor an improved tax and regulatory environment for business and oppose having the government borrow more to fund additional social services and public goods. Of course, as more and more "liberals" have listened to the call for a target growth path for spending on output, it is possible that there are growing numbers of "Market Monetarists" who support increased regulation and provision of government services.

If there was an improved tax and regulatory environment for business, along with a return to a growth path for nominal GDP starting above its current level but no higher than that of the Great Moderation, then the demand for credit would grow both because of the improved monetary regime and the improved business climate. Nominal and real interest rates would rise more quickly than if "anti-business" policies the polices remain in force. The improved productivity would result in more of the expansion in spending on output generating added production, and less creating inflation. That the increase in inflation would be smaller means that nominal interest rates might rise less quickly and real interest rates more quickly. I think most Market Monetarists would consider this a good thing.

On the other hand, if the liberal approach of expanding the size of government occured in combination with an appropriate target growth path for nominal GDP, then the added demand for credit by government, combined with growing private sector demand due to expectations (and realized) growth in spending on output, would result in nominal and real interest rates rising faster than if the only change was an improved monetary regime. Unfortunately, the increase in the size of the public sector, given any growth path for nominal GDP, will probably result in a higher growth path of the price level (of private goods,) and higher inflation at some point. That implies higher nominal interest rates than otherwise--at least for a time.

Well...

Using a target policy interest rate to target inflation makes pro-business regulatory and tax reform look to be the only way to generate a more rapid recovery. It creates the needed spark to credit demand, and prevents spending growth from pushing up inflation. Maybe it is no surprise that Market Monetarists have trouble interesting conservatives in a new monetary regime that can keep spending growing at a slow steady rate despite existing "anti-business" tax and regulatory policies.

Using a target policy interest rate to target inflation and an output gap makes an increase in the size of government look to be the only way to generate a more rapid recovery. It creates the needed spark to credit demand, and we just have to put up with higher inflation. Maybe it is no surprise that Market Monetarists find that "liberals" keep on insisting the monetary policy is chancy, that it needs to be enhanced by debt-funded government spending, and that it only works by generating a higher inflation rate.

Maybe Market Monetarists need to appeal to a third force. Don't hold the economy hostage to the century long class warfare between the reds and blues?

However, the U.S. has a regime where the central bank likes to make periodic changes in the short and safe interest rate in order to target inflation and the output gap. Some conservatives are proposing that the output gap be dropped as a criterion, so the policy interest rate would solely be adjusted to maintain a stable inflation rate. Of course, the theory is that output gaps will push inflation away from target, and so targeting inflation automatically tends to close output gaps too.

What is the conservative approach to generating recovery? Improve the tax and regulatory climate for business. If business believes that they will be able to earn and keep more profit in the future, this will raise credit demand, even given expectations about depressed future sales. Credit demand currently depends on expectations about both future sales and the future business and regulatory climate. Improving one, given the other, should result in increased credit demand. Given the Fed's target for the interest rate, any increase in credit demand is supplied through added money creation, and tends to generate more spending on goods and services.

Unfortunately, the increased aggregate demand will tend to increase inflation. With an inflation targeting central bank, this would require an increase in the policy interest srate, which would offset the effect of the higher credit demand on spending. Of course, if inflation is currently running a bit below target, this would not be a problem.

Fortunately, the pro-business tax and regulatory changes have another effect. Not only does they tend to raise the demand for credit, they also enhance productivity, which implies an increase in aggregate supply. Now, if nominal aggregate expenditure continue on an unchanged growth path, the result of the improved supply condition would be a more rapid expansion of output and slower inflation. But with inflation targeting, instead the enhanced productivity allows for more rapid growth in nominal expenditure.

So, the improved tax and regulatory environment raises both credit demand and productivity, allowing for a more rapid recovery of spending and production at a given target for the policy rate and a given target for the inflation rate. Also, the recovery in expenditure would be self-reinforcing. That is, when firms borrow more and spend more because an improved business climate , the resulting increased sales spur further increases in credit demand. When all of this happens, it is almost certain that the policy rate would need to increase, so that spending on output doesn't grow faster than justified by the increases in productivity.

Therefore, with an improved tax and regulatory environment a rapid recovery can be generated even if the central bank targets some short and safe interest rate to keep inflation at a low and stable rate. What could go wrong? The resulting increase in credit demand and enhancement of productivity might be too small to generate a "sufficient" recovery.

What is the "liberal" approach to economic recovery? The government should borrow money and spend it on expanded social services and "public goods." The public goods would include subsidies for private goods that provide external benefits. This provides a demand for credit by the government and given the target for the policy rate, this is expansionary. New money is being created for the government to spend. While it is conceivable that the public investments would add to productivity, (certainly some could,) the typical investment is supposed to improve the quality of life for at least some segment of the population. Enhancing the ability of firms to produce the sorts of private goods whose prices are included on price indices is of secondary interest.

If inflation is currently below target, the inflationary impact of added spending on prices isn't much of a problem. Increased government spending and borrowing will raise credit demand at the target for the policy rate and spending on output. Inflation will pick up back to target at the same time real output and employment recover. However, if inflation is on target, then it is essential, from the "liberal" perspective, that the "output gap" count as a weighting factor, so that higher inflation would be permitted, at least temporarily. The gap of inflation above target would be accepted because it would reduce the gap of real output below potential. Better yet, the central bank could just raise its inflation target.

Both the "conservative" and "liberal" solutions involve policies that they support anyway. The sluggish recovery is being used as an excuse for their preferred policies. Also, the policies of each are anathema to the other. Conservatives don't want to increase the size of government. One reason is that they are opposed to the changes in taxes that would be needed to pay for it sooner or later. Liberals don't want to improve the tax and regulatory environment for business, since creating such burdens to provide benefits to favored groups (the poor and working class) is central to their purpose.

Probably most Market Monetarists favor an improved tax and regulatory environment for business and oppose having the government borrow more to fund additional social services and public goods. Of course, as more and more "liberals" have listened to the call for a target growth path for spending on output, it is possible that there are growing numbers of "Market Monetarists" who support increased regulation and provision of government services.

If there was an improved tax and regulatory environment for business, along with a return to a growth path for nominal GDP starting above its current level but no higher than that of the Great Moderation, then the demand for credit would grow both because of the improved monetary regime and the improved business climate. Nominal and real interest rates would rise more quickly than if "anti-business" policies the polices remain in force. The improved productivity would result in more of the expansion in spending on output generating added production, and less creating inflation. That the increase in inflation would be smaller means that nominal interest rates might rise less quickly and real interest rates more quickly. I think most Market Monetarists would consider this a good thing.

On the other hand, if the liberal approach of expanding the size of government occured in combination with an appropriate target growth path for nominal GDP, then the added demand for credit by government, combined with growing private sector demand due to expectations (and realized) growth in spending on output, would result in nominal and real interest rates rising faster than if the only change was an improved monetary regime. Unfortunately, the increase in the size of the public sector, given any growth path for nominal GDP, will probably result in a higher growth path of the price level (of private goods,) and higher inflation at some point. That implies higher nominal interest rates than otherwise--at least for a time.

Well...

Using a target policy interest rate to target inflation makes pro-business regulatory and tax reform look to be the only way to generate a more rapid recovery. It creates the needed spark to credit demand, and prevents spending growth from pushing up inflation. Maybe it is no surprise that Market Monetarists have trouble interesting conservatives in a new monetary regime that can keep spending growing at a slow steady rate despite existing "anti-business" tax and regulatory policies.

Using a target policy interest rate to target inflation and an output gap makes an increase in the size of government look to be the only way to generate a more rapid recovery. It creates the needed spark to credit demand, and we just have to put up with higher inflation. Maybe it is no surprise that Market Monetarists find that "liberals" keep on insisting the monetary policy is chancy, that it needs to be enhanced by debt-funded government spending, and that it only works by generating a higher inflation rate.

Maybe Market Monetarists need to appeal to a third force. Don't hold the economy hostage to the century long class warfare between the reds and blues?

Friday, July 6, 2012

Noah Smith on Futures Targeting

Noah Smith wrote a critique of Scott Sumner's proposal to use futures contracts on nominal GDP to target the growth path of nominal GDP. Unfortunately, his understanding of the proposal came from Williamson's brief description. Smith discusses a proposal to control monetary policy according to changes in the price of a futures contract. The central bank would observe the price at which private investors trade a futures contract, and then use that to gauge appropriate changes in monetary policy.

Smith argues that monetary policy would be very volatile--the central bank would have to tighten or loosen large amounts. He makes this judgement based upon the volatility of stock prices relative to the discounted value of dividends. Since stock prices vary much more than discounted dividends, then futures contracts on nominal GDP would vary more than nominal GDP. He then notes that nominal GDP has been very volatile (though using Williamson's peculiar measure.) And so, the futures prices would be extremely volatile.

It is certainly good to see more outside criticism of futures targeting. Unfortunately, it is important to review what the proponents have said rather than just riffing off what other critics have said. Sumner proposes having the central bank buy and sell the futures contract at a target price. There would be zero volatility in the price of the futures contract.

I believe that Sumner has in mind a system where the target price increases at a 5% annual rate. However, it would also be possible to define an index by dividing the actual value of nominal GDP by the target, which would mean that the price of the future contract would never change.

Of course, what this means is that the central bank always takes a position opposite to the net position of market traders. If there are more bulls than bears on the market, the Fed must be a bear too. If there are more bears than bulls, the Fed must be a bull. Smith's argument would then be that because stock prices vary more than actual dividends, the Fed's position on the futures contracts would vary more than actual fluctuations of nominal GDP. Since nominal GDP varies so much, then the Fed's position on the contracts would vary a tremendous amount.

There are several problems with his argument.

Estimates of nominal GDP volatility from periods when the central bank was targeting some combination of inflation and the output gap, targeting the unemployment rate and allowing accelerating nominal GDP growth, and targeting some combination of inflation and interest rates (explicitly to help the Treasury fund deficits, no less,) are not likely to help predict actual nominal GDP volatility under a monetary regime that solely targets the growth path of nominal GDP.

To the degree that stock volatility is generated by momentum trading (foolish investors buying stock because it provided capital gains in the past,) or some kind of "greater fool" process, (clever investors buying over-valued stock planning to unload it to really foolish investors,) or even clever people playing some zero sum "musical chairs" game, none of that applies to an index futures contract with a fixed price. The contracts only provide a payoff if nominal GDP actually deviates from target in the direction predicted by the trader. If it goes the other way, there are losses and with no change, there is no gain, just wasted transactions costs.

I would think that comparing the volatility of stocks to the volatility of dividends is not just looking at excessive volatility in stocks, but also at the theory that stock only has value if profits are paid out to the stockholders in the form of dividends. The notion that stockholders accept that profits are retained forever and any one stockholder can only cash in by selling shares, is also being tested. Suppose that certain blue chip companies pay out regular dividends, hoping to attract investors who see the stock as providing stable income, almost like a bond. Other companies keep just about all profits and reinvest them. Dividends are remarkably stable (perhaps more so than earnings.) Stock values vary depend ing on expected earnings. (Of course, maybe Smith misspoke and he meant that stock prices are remarkably more volatile than earnings .rather than dividends.)

Also, discounting observed dividends by a variety of discount rates, and comparing that to stock price volatility seems to assume that discount rates are stable. Isn't the hypthosesis that there is a discount rate being tested? I would think that one of the things that impact stock price volatility is changes in expected future discount rates.

Most importantly, stocks form an important store of wealth for many people. They have a long record of providing positive returns one way or another. People storing wealth in this way have any number of personal reasons to buy or sell. Further, the prices do change, and trying the beat the market is always a temptation. Nominal GDP futures are a bet on whether nominal GDP will be on target or not. If the system works perfectly, the expected return would be zero. It is hard to see why these contracts would form an important store of wealth.

All of the proposals for futures targeting involve having the central bank change current monetary policy according to changes in its position on the futures contract. If the market is long, and the central bank is short, then it should tighten. If the market is short, and the central bank is long, then it should loosen. The problem that concerns Smith is that the market position on the contract can be expected to vary more than the true expected value of nominal GDP away from target, (which means more than the expected payoffs) and so the central bank will be loosening and tightening more than necessary. And even if nominal GDP stays on target, this offsetting loosening and tightening seems scary. Well, let's change "scary" to "might be disruptive to real economic activity," or "somewhat or substantially reduce human welfare."

Smith suggests that this volatility in central bank policy would be quarter by quarter. There would be a quarter of tight monetary policy followed by a quarter of loose monetary policy. Most proposals for futures targeting involve continuous adjustment. The central bank trades the future all during the quarter and makes open market operations according to its position on the contract. In other words, rather than the trades last quarter determining whether policy is tight this quarter, trades early today are determining monetary conditions later in the day. Trades late in the day determine monetary conditions tomorrow morning.

Sumner has proposed discrete trading, but on a daily basis. The central bank announces a tentative daily target for base money, the contracts are traded, and then the Fed adjusts the tentative target by the net position on the contract. Perhaps the futures contract trades in the morning, and then open market operations in bonds occur in the afternoon.

This doesn't mean that there would be no volatility. On the contrary, my point is that all of these proposals would allow for volatility to occur during each quarter, each month, and each week. And with the more continuous proposals--during each day.

To some degree, this high frequency volatility is even more "scary," but not necessarily. Wouldn't such fluctuations would be over before there was much chance for it to do harm? Still, I believe that the quantity of base money should adjust to the demand to hold it, conditional on the nominal anchor. And the least bad nominal anchor is slow steady growth of spending on output--a nominal GDP target. To the degree trades of the future contract causes an excess supply of base money for the first part of the week, even if there is an offsetting excess demand at the end of the week, it would be undesirable.

These shortages and surpluses of base money would certainly cause liquidity effects on interest rates, and so there would be undesirable volatility in short term interest rates. Now, I don't think that stable short term interest rates are necessarily desirable. I think that short term interest rates should fluctuate due to short term changes in the supply and demand for credit. If many people want to borrow this week, and few want to lend, having interest rates a bit higher this week, so some of those wanting to borrow wait a bit, and who were going to lend next week, bring forward their lending to this week, is desirable.

Still, it is hard to see how significant volatility would be introduced into short term interest rates, much less long term rates, by high frequency changes in the monetary base. It would rather be expectations of persistent changes in the monetary base due to persistent shifts in the market position on the contract that would have have persistent effects on financial markets and then spending on output.

Of course, most criticisms of the proposal have been that no one will be motivated to trade the contract, not that they will do a lot of trading for reasons that have nothing to do with expectations of nominal GDP relative to target.

Anyway, my own view is that the central bank should be free to adjust monetary conditions as it sees fit, subject to the constraint that it trade the futures contract at the target price. If it turned out that a short position by the market today was likely to be followed by a long position by the market tomorrow, then making open market purchases today just to sell them tomorrow would be pointless. (Part of my mindset continues to be consideration of a purely privatized version of index futures convertibility, where all the competing issuers of money are free to choose their positions on the contract just like anyone else.)

Finally, if futures targeting worked, wouldn't the variation of the central bank's position on the contract vary more than nominal GDP? It is supposed to provide a negative feedback mechanism. Monetary conditions today are adjusted according to market expectations of future nominal GDP as revealed by the market position on the futures contract. If it works, nominal GDP must actually have less volatility than the the market position on the contract. Suppose nominal GDP varied, but the central bank's position on the contract always stayed zero. Would that be a good thing?

Noahpinion: Excess volatility and NGDP futures targeting

Smith argues that monetary policy would be very volatile--the central bank would have to tighten or loosen large amounts. He makes this judgement based upon the volatility of stock prices relative to the discounted value of dividends. Since stock prices vary much more than discounted dividends, then futures contracts on nominal GDP would vary more than nominal GDP. He then notes that nominal GDP has been very volatile (though using Williamson's peculiar measure.) And so, the futures prices would be extremely volatile.

It is certainly good to see more outside criticism of futures targeting. Unfortunately, it is important to review what the proponents have said rather than just riffing off what other critics have said. Sumner proposes having the central bank buy and sell the futures contract at a target price. There would be zero volatility in the price of the futures contract.

I believe that Sumner has in mind a system where the target price increases at a 5% annual rate. However, it would also be possible to define an index by dividing the actual value of nominal GDP by the target, which would mean that the price of the future contract would never change.

Of course, what this means is that the central bank always takes a position opposite to the net position of market traders. If there are more bulls than bears on the market, the Fed must be a bear too. If there are more bears than bulls, the Fed must be a bull. Smith's argument would then be that because stock prices vary more than actual dividends, the Fed's position on the futures contracts would vary more than actual fluctuations of nominal GDP. Since nominal GDP varies so much, then the Fed's position on the contracts would vary a tremendous amount.

There are several problems with his argument.

Estimates of nominal GDP volatility from periods when the central bank was targeting some combination of inflation and the output gap, targeting the unemployment rate and allowing accelerating nominal GDP growth, and targeting some combination of inflation and interest rates (explicitly to help the Treasury fund deficits, no less,) are not likely to help predict actual nominal GDP volatility under a monetary regime that solely targets the growth path of nominal GDP.

To the degree that stock volatility is generated by momentum trading (foolish investors buying stock because it provided capital gains in the past,) or some kind of "greater fool" process, (clever investors buying over-valued stock planning to unload it to really foolish investors,) or even clever people playing some zero sum "musical chairs" game, none of that applies to an index futures contract with a fixed price. The contracts only provide a payoff if nominal GDP actually deviates from target in the direction predicted by the trader. If it goes the other way, there are losses and with no change, there is no gain, just wasted transactions costs.

I would think that comparing the volatility of stocks to the volatility of dividends is not just looking at excessive volatility in stocks, but also at the theory that stock only has value if profits are paid out to the stockholders in the form of dividends. The notion that stockholders accept that profits are retained forever and any one stockholder can only cash in by selling shares, is also being tested. Suppose that certain blue chip companies pay out regular dividends, hoping to attract investors who see the stock as providing stable income, almost like a bond. Other companies keep just about all profits and reinvest them. Dividends are remarkably stable (perhaps more so than earnings.) Stock values vary depend ing on expected earnings. (Of course, maybe Smith misspoke and he meant that stock prices are remarkably more volatile than earnings .rather than dividends.)

Also, discounting observed dividends by a variety of discount rates, and comparing that to stock price volatility seems to assume that discount rates are stable. Isn't the hypthosesis that there is a discount rate being tested? I would think that one of the things that impact stock price volatility is changes in expected future discount rates.

Most importantly, stocks form an important store of wealth for many people. They have a long record of providing positive returns one way or another. People storing wealth in this way have any number of personal reasons to buy or sell. Further, the prices do change, and trying the beat the market is always a temptation. Nominal GDP futures are a bet on whether nominal GDP will be on target or not. If the system works perfectly, the expected return would be zero. It is hard to see why these contracts would form an important store of wealth.

All of the proposals for futures targeting involve having the central bank change current monetary policy according to changes in its position on the futures contract. If the market is long, and the central bank is short, then it should tighten. If the market is short, and the central bank is long, then it should loosen. The problem that concerns Smith is that the market position on the contract can be expected to vary more than the true expected value of nominal GDP away from target, (which means more than the expected payoffs) and so the central bank will be loosening and tightening more than necessary. And even if nominal GDP stays on target, this offsetting loosening and tightening seems scary. Well, let's change "scary" to "might be disruptive to real economic activity," or "somewhat or substantially reduce human welfare."

Smith suggests that this volatility in central bank policy would be quarter by quarter. There would be a quarter of tight monetary policy followed by a quarter of loose monetary policy. Most proposals for futures targeting involve continuous adjustment. The central bank trades the future all during the quarter and makes open market operations according to its position on the contract. In other words, rather than the trades last quarter determining whether policy is tight this quarter, trades early today are determining monetary conditions later in the day. Trades late in the day determine monetary conditions tomorrow morning.

Sumner has proposed discrete trading, but on a daily basis. The central bank announces a tentative daily target for base money, the contracts are traded, and then the Fed adjusts the tentative target by the net position on the contract. Perhaps the futures contract trades in the morning, and then open market operations in bonds occur in the afternoon.

This doesn't mean that there would be no volatility. On the contrary, my point is that all of these proposals would allow for volatility to occur during each quarter, each month, and each week. And with the more continuous proposals--during each day.

To some degree, this high frequency volatility is even more "scary," but not necessarily. Wouldn't such fluctuations would be over before there was much chance for it to do harm? Still, I believe that the quantity of base money should adjust to the demand to hold it, conditional on the nominal anchor. And the least bad nominal anchor is slow steady growth of spending on output--a nominal GDP target. To the degree trades of the future contract causes an excess supply of base money for the first part of the week, even if there is an offsetting excess demand at the end of the week, it would be undesirable.

These shortages and surpluses of base money would certainly cause liquidity effects on interest rates, and so there would be undesirable volatility in short term interest rates. Now, I don't think that stable short term interest rates are necessarily desirable. I think that short term interest rates should fluctuate due to short term changes in the supply and demand for credit. If many people want to borrow this week, and few want to lend, having interest rates a bit higher this week, so some of those wanting to borrow wait a bit, and who were going to lend next week, bring forward their lending to this week, is desirable.

Still, it is hard to see how significant volatility would be introduced into short term interest rates, much less long term rates, by high frequency changes in the monetary base. It would rather be expectations of persistent changes in the monetary base due to persistent shifts in the market position on the contract that would have have persistent effects on financial markets and then spending on output.

Of course, most criticisms of the proposal have been that no one will be motivated to trade the contract, not that they will do a lot of trading for reasons that have nothing to do with expectations of nominal GDP relative to target.

Anyway, my own view is that the central bank should be free to adjust monetary conditions as it sees fit, subject to the constraint that it trade the futures contract at the target price. If it turned out that a short position by the market today was likely to be followed by a long position by the market tomorrow, then making open market purchases today just to sell them tomorrow would be pointless. (Part of my mindset continues to be consideration of a purely privatized version of index futures convertibility, where all the competing issuers of money are free to choose their positions on the contract just like anyone else.)

Finally, if futures targeting worked, wouldn't the variation of the central bank's position on the contract vary more than nominal GDP? It is supposed to provide a negative feedback mechanism. Monetary conditions today are adjusted according to market expectations of future nominal GDP as revealed by the market position on the futures contract. If it works, nominal GDP must actually have less volatility than the the market position on the contract. Suppose nominal GDP varied, but the central bank's position on the contract always stayed zero. Would that be a good thing?

Noahpinion: Excess volatility and NGDP futures targeting

Thursday, July 5, 2012

Finished The Great Recession by Hetzel

I just finished Robert Hetzel's The Great Recession: Market Failure or Policy Failure. Hetzel is an advocate of what he describes as the monetary view. In this view, the market system will generate real interest rates that maintain full employment of resources in the absence of monetary disturbances. In a modern fiat currency system, monetary disturbances are solely the responsibility of the central bank. By using its ability to avoid monetary disturbances, the central bank can allow the market system to generate real interest rates that maintains full employment.

How is a central bank to avoid monetary disturbances? Hetzel insists that it must create a nominal anchor, and proposes that expected inflation is appropriate. Interestingly, he is critical of the Fed adopting a 2% inflation target rather than promoting price stability. So, with a goal of a stable expected inflation rate of presumably zero, the central bank can then let the actual price level fluctuate according to random shocks. (Presumably these would be supply shocks, but perhaps demand shocks due to errors would also be ignored.) The central bank then changes its interest rate target according to sustained changes in the demand for resources. These adjustments in the policy rate generate real interest rates consistent with full employment of resources.

It sounds a bit like a Taylor rule to me, but Hetzel criticizes the Taylor rule. How is the Greenspanesque sustained changes in the demand for resources different from an output gap? To me, it is the same idea, but I suppose Hetzel sees the output gap as something more concrete. Maybe last quarter's estimate of real GDP less the CBO estimate of potential output. I suppose Hetzel would similarly be critical of using last month's measure of the CPI or CEP to measure inflation. Allowing random fluctuations of the price level in the context of a commitment to a stable price level is also rather Greenspanesque.

Hetzel is very critical of what he calls the credit view, and often adds in the Keynesian view as another equally bad perspective. These views are that the market system is inherently unstable so that central bankers must be given complete discretion to manage the economy. In particular, central bankers must prevent excessive use of debt to fund speculation. If they let that happen, then there is no option but to suffer through a recession to purge all the excesses. Hetzel provides plenty of evidence that that Fed caused the Great Depression as an unintended byproduct of its effort to curb excess credit to fund stock market speculation. And then, allowed the economy collapse, treating it as the unavoidable consequence of that prior speculation. Further, it aborted recovery due to worries of excessive credit funding too much speculation. As for Keynes, Hetzel sees worries about fluctuations in the animal spirits of investors as being the same foolishness in another guise.

Hetzel argues that fractional reserve banking isn't especially unstable. He is very concerned with the moral hazard created by bailouts. He certainly grants that insolvent banks are subject to runs, and depositors that expect to be bailed out will fund banks that are poorly-capitalized and take excessive risks. But in a regime where banks depositors don't expect bailouts, banks are less likely to become insolvent. And when conservatively-managed, well-capitalized banks do become insolvent, it is those banks that suffer runs, not all banks.

Hetzel builds a convincing case that Friedman and Schwartz were mistaken in blaming bank runs for the severity of the Great Depression. According to Hetzel, a monetary disturbance caused the Great Depression, and only as the Great Depression made banks insolvent, were they subject to runs. Rather than the Bank of United States failing, and all the ignorant depositors at other banks withdrawing their funds, bank runs only occurred gradually, here and there, with very specific solvency problems developing.

Hetzel draws parallels between the credit view during the Great Depression, and the credit views of the Great Recession. He rejects the notion that excessive credit to fund speculation in housing caused the Great Recession. Instead, he blames the failure of the Fed to reduce interest rates in the face of economic weakening in 2008 largely due to worries about rising oil prices. In Hetzel's view, shifts in oil prices should be allowed to cause the price level to change,. These are the permitted "random" fluctuations in the price level in the context of a long run commitment to stable prices. The policy rate should have been reduced because of the sustained reduction in the demand for resources.

As for the financial crisis, he explains that as being due to discretionary changes in expected bailout policy. If financial markets had always been based upon making debtors take losses, there would have been no problem. No financial panic and not very many insolvencies. If the "bailout everyone" policy had been continued, there could have been insolvencies of reckless and poorly-capitalized financial firms, but no financial panic. It was the discretionary approach of first bailing out Bear Stearn and then not bailing out Lehman Brothers that caused the financial crisis. Still, the Great Recession wasn't caused by that crisis. And the Fed's focus on fixing financial markets did little good. The problem was the monetary disturbance--failure to adjust the policy rate so avoid sustained changes (decreases) in the demand for resources, in the context of a long run commitment to stable prices.

In my view, Hetzel should take the next step. He should adopt nominal GDP level targeting as a proposed rule. While the credit view may be wrongheaded and worries about animal spirits overdone, the only way these could cause generalized shifts in the demand for output is by impacting the quantity of money or the demand to hold it. These are perhaps wrongheaded theories of what causes monetary disturbances. And all monetary disturbances have monetary solutions. As a practical matter, keeping nominal GDP growing on a targeted path in the face of credit-fueled speculation, deleveraging, or changes in animal spirits is the least bad option.

Hetzel does mention sometimes that the Fed should be focusing on increasing or maintain spending on output. But it is almost like reading Milton Friedman. There are hints, but it in the end, the rules are about the price level. Take the leap. Target the level of spending on output--nominal GDP.

Hetzel insists that the market should generate a real interest rate to maintain full employment. If think he focuses too much on interest rates. While adjusting a policy interest rate according to changes in the demand for resources does seem like a way of getting at the appropriate interest rate, it is hardly market determined. Of course, other interest rates--particularly longer term to maturity ones--would be market determined. And admittedly, there may be no better alternative. Adjusting the quantity of base money according to the demand to hold it is difficult too. As Hetzel mentions, estimating money demand is not easy. (Hetzel doesn't discuss his proposal to target expected inflation as calculated using TIPs, much less index futures targeting as proposed by Sumner.)

Even in the extreme case, where the shadow equilibrium real interest rate on hand-to-hand currency is negative, the problem is still monetary. The argument shouldn't be that in the absence of monetary disturbances, the equilibrium interest rate on all financial instruments, no matter how short or safe, will always be positive. It is rather that the only way these sorts of problems caused general gluts of goods is because they lead, either directly or indirectly, to a shortage of money. And fixing such shortages of money (and avoiding surpluses) is the key role of a monetary regime.

How is a central bank to avoid monetary disturbances? Hetzel insists that it must create a nominal anchor, and proposes that expected inflation is appropriate. Interestingly, he is critical of the Fed adopting a 2% inflation target rather than promoting price stability. So, with a goal of a stable expected inflation rate of presumably zero, the central bank can then let the actual price level fluctuate according to random shocks. (Presumably these would be supply shocks, but perhaps demand shocks due to errors would also be ignored.) The central bank then changes its interest rate target according to sustained changes in the demand for resources. These adjustments in the policy rate generate real interest rates consistent with full employment of resources.

It sounds a bit like a Taylor rule to me, but Hetzel criticizes the Taylor rule. How is the Greenspanesque sustained changes in the demand for resources different from an output gap? To me, it is the same idea, but I suppose Hetzel sees the output gap as something more concrete. Maybe last quarter's estimate of real GDP less the CBO estimate of potential output. I suppose Hetzel would similarly be critical of using last month's measure of the CPI or CEP to measure inflation. Allowing random fluctuations of the price level in the context of a commitment to a stable price level is also rather Greenspanesque.